In films such as Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps and Social Network, Hollywood is showing secular capitalism changing America’s motto to “In Greed We Trust.” In the summer of 2010, the US Congress passed a twenty-three-hundred-page act to regulate the financial sector. This act is an admission of the massive corruption in that sector of the economy. Wall Street’s corruption, however, has yet to become a part of Main Street. The traditional morality of the West, easily evident in small towns and villages is incomprehensible to most non-Western visitors.

For example, in 1982, I was traveling to England for a conference on economic development. Leaving New Delhi after midnight, I was sleepy, but the Sikh gentleman next to me talked nonstop. He was returning to England after visiting his parents in a Punjab village in northwest India. He could not comprehend why I was living in poverty, serving the poor. He took it as his mission to persuade me to settle in England. Doing business in England, he argued, was easy and profitable. After being harassed for more than an hour, I began to lose my patience. But something intrigued me. He could not speak a single sentence without making a mistake. How could someone who spoke such poor English succeed as a businessman in England? So I asked, “Tell me, sir, why is business so easy in England?”

“Because everyone trusts you there,” he answered, without pausing for a moment. Having not yet ventured into a business, I did not grasp how important trust was to success in business. I pushed back my seat and went to sleep. After the conference, Mr. Jan van Barneveld hosted me in his home at Doorn, Holland.

One afternoon Jan said to me, “Come let us get some milk.” We walked between gorgeous moss-covered trees to a dairy farm. I had never seen anything like this: a neat and tidy dairy farm with about one hundred cows but no human beings. The cows were milked automatically, and the milk was pumped into a large boiler-like tank.

We entered the milk room, where Jan opened the tap and filled his jug. Then he reached out to a windowsill and pulled down a bowl full of cash. He took out his wallet, drew a twenty guilder note, and put it into the bowl. He helped himself to the change from the bowl, put it into his wallet, picked up the jug, and started to walk out. I couldn’t believe my eyes. “Man,” I said, “if you were an Indian, you would take the milk and the money!” Jan laughed. But in that instant, I understood what that Sikh businessman had been trying to tell me.

If this was India and I walked out with the money and the milk, the dairy owner would need to hire a cashier. Who would pay for the cashier? I, the consumer, would; and the price of milk would go up. But if the consumer were corrupt, why should the dairy owner be honest? He would add water to the milk to make more money. I would then be paying more for adulterated milk. I would complain, “The milk is adulterated; the government must appoint inspectors.”

Who would pay for the inspectors? I, the taxpayer, would. But if the consumer, producer, and the supplier were corrupt, why should the inspectors be honest? They would extract bribes from the supplier. If he did not bribe them, the inspectors would delay the supply and ensure that the milk curdled before it got to me.*

*Most of the world does not have refrigerated vans and storage facilities for milk.

Who would pay for the bribe? Again, I, the consumer, would pay the additional cost. By the time I paid for the milk, the cashier, the water, the inspector, and the bribe, I would have little money left to buy chocolate for the milk—so my children would not drink the milk and would be weaker than the Dutch children. Having spent extra money on the milk, I would not be able to take my children out for ice cream. The cashier, water, bribe, and inspector add no value to the milk. The ice-cream industry does. My corruption keeps me from patronizing a value-adding business. That reduces our economy’s capacity to create jobs.

Some years ago I shared this story in a conference in Indonesia. An Egyptian participant laughed the most. As all eyes turned to him, he explained, “We Egyptians are cleverer than these Indians. If no one was watching, we would take the milk, the money, and the cows.” The gentleman was too charitable toward us Indians.

Cynicism in India

Many years after my trip to Holland, I heard “uncle” Emmanuel* complain that they were getting highly adulterated milk in Mussoorie. I told him that Ruth had finally found an honest milkman and that we were getting pure milk. After I had spent half an hour trying to persuade the uncle that they should buy milk from our milkman, he got tired and dismissed me as utterly naïve. “It’s impossible to get pure milk in Mussoorie,” he said. “Your milkman must be very clever. He must be adding something other than water to the milk, something that you haven’t figured out as yet.”

*Father-in-law to my older brother and younger sister.

Taking the hint, I changed the conversation to the question of corruption. Uncle, a retired railway engine driver, told me that he had just heard from a friend of his (also a retired driver) that his son had spent nine months and thirty thousand Indian rupees in bribes and still had not gotten a job with the railways. This was in spite of the policy that after an employee retires, one of his children will be given preference in recruitment. Then uncle described at length how he became employed in the 1940s. Here’s the abridged version.

The British were ruling India. The recruiting officer examined his certificates, ordered an immediate in-house physical checkup, offered him a cup of tea, looked at the doctor’s report, and ordered that an appointment letter be given to him the next day. The following morning the clerk issued the appointment letter with another cup of tea! No bribes, no strings pulled, and no delays.

Recruitment was a clean, prompt, and professional affair, based solely on merit. The consequence was competent employees who were loyal to the enterprise, proud of their work, and respectful of law, authority, and the government. That era, the uncle lamented, had gone for good. Fifty years of independence offered no hope for the future.

The Effect of Corruption

Transparency International (TI), a German nongovernmental organization, has long recognized the correlation between corruption and poverty. Each year TI publishes a Global Corruption Perception Index (CPI) that ranks countries from the least corrupt to the most corrupt. The index for 2009 ranks 180 countries, with 10 points allotted for a totally clean country. No country, of course, gets 10 points; majority of the countries receive fewer than 5 points—meaning that they are more corrupt than clean. Here are extracts from the 2009 rankings:

[[DESIGN: TABLE DOES NOT HAVE TO HAVE GRIDLINES.]]

Rank Country CPI 2009 Score (out of 10 points)

1 New Zealand 9.4

2 Denmark 9.3

3 Singapore 9.2

17 United Kingdom 7.7

19 United States 7.5

79 China 3.6

84 India 3.4

146 Russia 2.2

176 Iraq 1.5

179 Afghanistan 1.3

180 Somalia 1.1Does poverty cause corruption? Or does corruption cause poverty? Whether the chicken comes first or the egg is an interesting, but theoretical question. Peter Eigen, TI chairman in 2002, emphasized the role corruption plays in keeping countries poor:

Political elites and their cronies continue to take kickbacks at every opportunity. Hand in glove with corrupt business people, they are trapping whole nations in poverty and hampering sustainable development. Corruption is perceived to be dangerously high in poor parts of the world, but also in many countries whose firms invest in developing nations . . . Politicians increasingly [emphasis mine] pay lip service to the fight against corruption but they fail to act on the clear message of TI’s CPI: that they must clamp down on corruption to break the vicious cycle of poverty and graft . . . Corrupt political elites in the developing world, working hand-in-hand with greedy business people and unscrupulous investors, are putting private gain before the welfare of citizens and the economic development of their countries.1

Wall Street in Crisis: A Perfect Storm Looming.

, ORC International conducted a confidential online survey of 250 respondents who work in the financial services industry. These respondents were employed as traders, portfolio managers, investment bankers, hedge fund professionals, financial analysts, investment advisors, asset managers, and stock brokers.

Labaton Sucharow, the law firm that established the first national practice exclusively dedicated to representing SEC whistleblowers, announced the results of its second survey of the U.S. financial services industry in July 2013. The survey confidentially polled financial professionals on corporate ethics, wrongdoing in the workplace and the role of financial regulators in policing the marketplace. The results suggest that the financial services industry faces a serious and growing ethical crisis.

An Industry in Crisis

The independent survey was conducted during June 18-27, 2013. It showed that 52% of the respondents believe that their competitors engaged in illegal or unethical behavior while 24% felt employees in their own company had engaged in similar misconduct. An astonishing 23% reported that they had observed or had first-hand knowledge of wrongdoing in the workplace and 29% believed that financial services professionals may need to engage in illegal or unethical behavior to be successful. An alarming 28% felt the industry does not put the interests of clients first and 24% admitted they would engage in insider trading if they could get away with it. Surprisingly, in response to each of these questions, younger professionals on Wall Street were significantly more likely to be aware, accept and engage in illegal or unethical conduct than their more senior colleagues.

"Many in the financial services industry appear to have lost their moral compass, and younger professionals pose the greatest threat to investors," said Jordan Thomas, partner and chair of the Whistleblower Representation practice at Labaton Sucharow. "Wall Street needs to take the first step toward recovery and admit that it has a corporate ethics problem, or Main Street should brace itself for more scandals."

"Our survey suggests there is a big disconnect between what the financial services industry preaches and what it actually does," said Chris Keller, partner and head of case development at Labaton Sucharow, in the release. "Until a culture of integrity and stewardship is established, investors will be at risk."

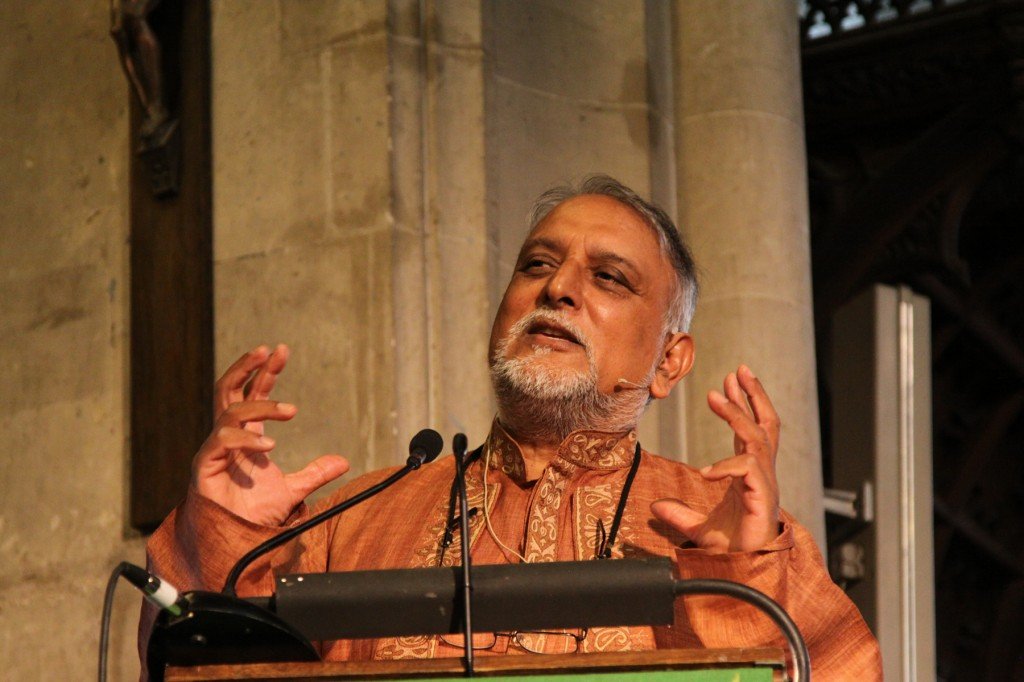

Vishal Mangalwadi is the author of

The Book That Made Your World: How the Bible Created the Soul of Western Civilization. (Thomas Nelson, 2011)

Be First to Comment