For a long time now we have been gravitating toward 1940s movies even though most of them were made before we were born. We like movies from this era because they tend to be more moral than many earlier and later movies. For one thing, there are consequences for actions. For another, successful, strong, and moral women are presented as the norm, especially during the

war years.

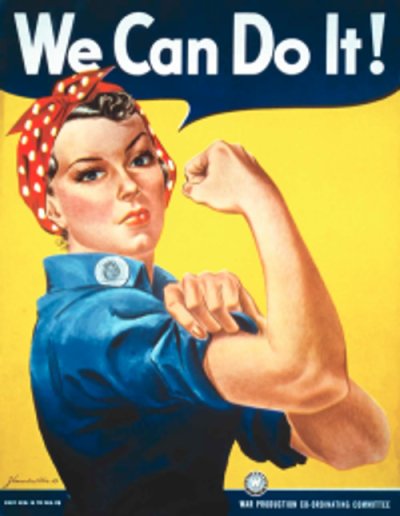

Ted Baehr, founder and publisher of Movieguide and chairman of the Christian Film and Television Commission, in his recent book :How to Succeed in Hollywood (Without Losing Your Soul)," confirms our preferences. He cites the noted singer and actor Pat Boone, who recalls the clean movies of yesteryear, in “the heyday of the film business,” when “families used to go together at least once a week to see a good movie in the neighborhood cinema.” “You could always count on it being a happy family experience…movies that don’t offend a large portion of their audience tend to make more money,” he adds, than those that “purposely insert foul language and other offensive material.”[1] When he was very young, Bill remembers his mother, who was a young working girl during the depression, loved to watch the Maisie movies whenever they would come on television. Bill would enjoy how much his mom would enjoy them, breaking in to tell him stories about her own experiences that paralleled Maisie’s. The heroine (played by the versatile Ann Sothern) was a type of “Rosie the Riveter” with a strong moral center. Maisie was always aggressive, forthright, sober (unless deceived), and moral. Her

prototype, Rosie the Riveter, was the symbol for World War II women who worked in the factories creating the equipment for the war effort. Rosie the Riveter had a strong work ethic with a solid moral center.

When the war ended, however, so did Rosie – and Maisie. They were replaced in the 1950s by “Blondie,” who was now limited to homemaking and sending the incompetent Dagwood to work. The message was that women were needed to step back and vacate jobs for returning male veterans. Had Rosie/Maisie been preserved, husband and wife could have split full-time jobs and

secured more family time.

And what about the classic Casablanca? Could such a movie have been made today? Wikipedia notes that “during scriptwriting, the possibility was discussed of Laszlo being killed in Casablanca, allowing Rick and Ilsa to leave together,” but was rejected so that Ilsa and Victor could “carry on with the work that in these days is far more important than the love of two little people,” as scriptwriter Casey Robinson explained to producer Hal Wallis. Further, “it was certainly impossible for Ilsa to leave Laszlo for Rick, as the production code forbade showing a woman leaving her husband for another man.”[2]

Today, however, we have no such restriction. Instead of welcoming the iconic film that it became, would today’s audiences have preferred the discussed ending? The Nineteen Forties’ context and code guided the filmmakers to choose the moral sacrifice, which took the film to a deeper level. The question for us, of course is - which ending would audiences choose today: the Christ sacrifice or the self-centered abandonment of virtue and loyalty for self-gratification?

In his book, Ted Baehr contrasts a “pagan” and a Christian “theology” of art. Steeped in pluralistic relativism, the current secularist

has lost the Christian moral center so “they have reinterpreted sin to mean politically incorrect speech, and carefully removed any burden of guilt from the family destroying sins of adultery and sodomy.” He cites Noam Chomsky, reputedly among the six most quoted historical thinkers, observing, “The United States is unusual among the industrial democracies in the rigidity of the system of ideological control – ‘indoctrination,’ we might say – exercised through the mass media.”[3]

A long-time friend of ours, Arch Davis of Davis Systems in Princeton, New Jersey, was once asked by an Afghan delegate to the United Nations where in the Bible Jesus condoned adultery. Our friend was surprised and assured him that could be found nowhere, since Jesus completely opposed adultery. The delegate was shocked. He explained that in Moslem countries the public

voice is one. The media reflects the government, which reflects the religion. Then he asked our friend why he supposed that the young zealots with all their lives ahead of them were willing to give up those lives as suicide bombers. He explained their sacrifice was to keep what they perceived to be the “pollution” of Christianity out of their countries. The Afghans and those like them assumed that all the adultery, violence, promoted dishonesty, disrespect, and moral laxity routinely served up as staples in United States’ films and fictional television shows is indicative of the values of our government, our people, our culture, and our religion.

We sow the wind of degradation and are shocked when we reap the whirlwind of extermination.

Ted Baehr, however, contrasts a Christian theology of the arts in “The Christian World View of Art and Communication,” a document whose forging he co-chaired for the Coalition on Revival. The Art and Communications Committee identified “God” as “the Author of creation and communication,” Jesus Christ as Lord over “all art and communication,” art as susceptible to “good and evil,” and needing to be harnessed as “expressions of God’s creativity” in human communication, and, thus, intended to “glorify God,” reflecting “the mind of Christ,” who “is the standard of excellence,” and, therefore, Christians in the arts should use their “great influence” to help our culture and its people shape a “view of reality,” submitted to “the lordship of Jesus Christ in accordance with His Word.”[4]

All of us know that no era in the fallen world is ever perfect, including the 1940s. But, as Ted Baehr and Pat Boone remind us, enough of the moral center was still apparent in films and radio stories of times like this to make many of us long for the type of morality promoted in these war time expressions of cinema art during the late 1930s through much of the 1940s. What did Maisie and Rosie have that we have lost? A moral center that portrayed them as independent, generous, and strong, matching hammer blow for hammer blow with the men at the front, while, at the same time, sober and serious, not jumping into bed with any man they dated, but, certainly in Maisie’s case, preserving sex strictly for marriage, her constant ideal in each of her

nine movies. What a Christian moral center teaches is that all of us are created by the one God who made all things “very good” (Genesis 1:27-28, 31). And we were created to steward this earth together, women with men. This is reality, so we need to ask ourselves some

serious questions about the way we portray reality: Do we reflect God’s good intentions in our movies for men and for women? Do we create and support movies with moral centers? Do we reflect faith/virtue in our media? And, if not, how do we recapture our

moral center in media, bringing this all under the lordship of Christ, who is our standard of excellence?

The Apostle Paul encouraged the Philippian church to think about “whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy” (Phil. 4:8). Those are the ideals we need to take with us to the multiplex.

William David Spencer, M.Div.,Th.M., Th.D.

Ranked Adjunct Professor of Theology and the Arts

[1] Ted Baehr, How to Succeed in Hollywood (Without Losing Your Soul) (Washington, D.C.: WorldNetDaily, 2011), xxv.

[2] en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casablanca_(film)#Initialresponse, accessed 26 August 2013.

[3] Ted Baehr, How to Succeed in Hollywood, 16.

[4] Ted Baehr, How to Succeed in Hollywood, 13-14.

Aida and William Spencer

Be First to Comment