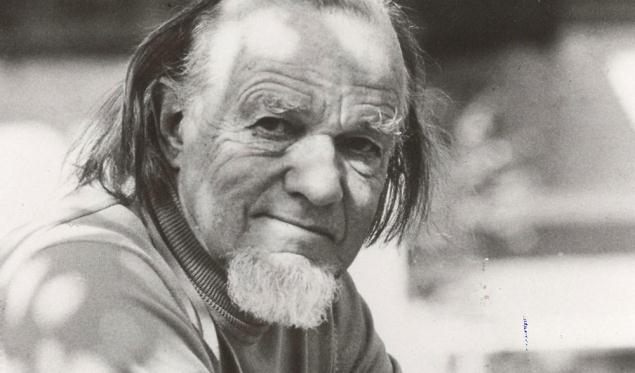

What is it about Francis Schaeffer that keeps books coming off the presses almost 30 years after his death?

Bill Edgar shows some reasons why in an effective new analysis, “Schaeffer on the Christian Life, Countercultural Spirituality.”

The first of a Crossway series, the book shows how the unusual man became so influential in American evangelical circles, even though he spent most of his life in the mountains of Switzerland.

To use an athletic analogy, Schaeffer could play several positions on the field, many of them as well as the specialists or experts.

He was an excellent evangelist. Many people came to salvation through the family ministry at L’Abri, which continues in Switzerland and several other places.

He was a first rate apologist for the Christian faith, engaging with disillusioned young people by talking to them about current events, the music of Bob Dylan or novels by Ken Kesey.

He was a disciplemaker, though he may not have thought of himself that way. Through friendships or mentoring or just his books, he helped train a next generation of believers who have grown in Christ and made major cultural and spiritual contributions – Charles Colson, Cal Thomas, Os Guinness, just to name a few who have gone on to help others also.

He was a compassionate pastor to the lost and hurting souls who came to L’Abri, sometimes under the influence of drugs and alcohol, other times confused by the ideas encountered in college and beyond. Is life really meaningless? Is there a basis for right and wrong? Says who and why?

Yet he approached these callings without much worry about the debates taking place in academic journals and universities.

Edgar, who teachers apologetics at Westminster Theological Seminary, writes biographically in the beginning, with useful personal memories of his own conversion at L’Abri and subsequent benefits from his association with Schaeffer and his wife Edith.

Some of the detail is interesting -- that Schaeffer was diagnosed as dyslexic. What an encouragement to anyone who has seen this challenge in a child. Could that explain something of Schaeffer’s patience and compassion for those with disabilities and his alertness to the problem of aborting children deemed less viable in the womb due to a handicap

The rest of the book reviews Schaeffer’s thinking, with an emphasis on True Spirituality, or a doctrine of growth in Christ that has never attracted as much attention as Schaeffer’s philosophical contributions or his conservative political bent in his later years.

Edgar shows how foundational this true spirituality was for the effectiveness of this man’s life. Naturally he attracted critics and jealousy. Yet even many of critics acknowledged that, humanly speaking, Schaeffer was the one who started the new conversations about Christ’s Lordship over art, music, literature, politics, ecology, philosophy, revival and reformation.

For those already familiar with Schaeffer’s life and thought, this book gives all kinds of new angles. It is a good companion to go with Barry Hankins’ 2008 conventional biography.

The book also is a good introduction for those who have never heard much about Francis Schaeffer and wonder what the fuss is all about 30 years after he died.

Edgar at first did not want to write the book. He did not think his friend and mentor was worthy of being included in a series with John Wesley, Martin Luther and C.S. Lewis.

“I thought he had neither the academic standing nor perhaps the influence wielded by these giants. His writings and films often seemed dated, and his principal legacy is no doubt people, not a movement based on revolutionary ideas,” Edgar confesses.

A little older and wiser, Edgar changed his mind. “A legacy of people is just the reason why. Schaeffer’s importance is because of the way he could take God, thinkers, and truth and make them so profoundly exciting – to people!”

His assessment: “Today I gladly agree that Schaeffer belongs to this hall of fame.”

Be First to Comment