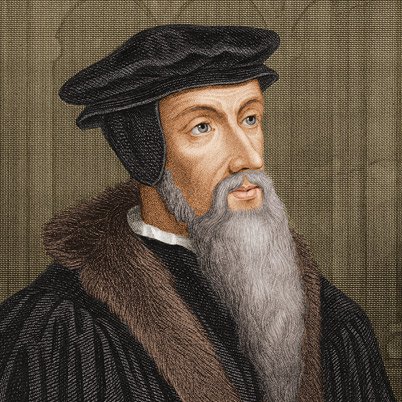

The religious and political ideology of the Founding Fathers stems partly from the ideas of one of the leaders of the Protestant Reformation, John Calvin. Even liberal historian Richard Hofstedter admits it.

Here’s what Calvin says about church and state:

"There is a twofold government in man: one aspect is spiritual, whereby the conscience is instructed in piety and in reverencing God; the second is political, whereby man is educated for the duties of humanity and citizenship that must be maintained among men. . . the former sort of government pertains to the life of the soul while the latter has to do with concerns of the present life. . . the former resides in the inner mind, while the latter regulates only outward behavior" (McNeill, Calvin, 847).

At one point, Calvin calls these two governments “the spiritual kingdom” and “the political kingdom” (Calvin, 847). Although he makes a distinction between these two kingdoms, Calvin also declares, “They are not at variance (Calvin, 1487)” because they are both instituted by God. That is why he admonishes his readers, “We are not to misapply to the political order the gospel teaching on spiritual freedom (Calvin, 847).” In other words, although we are saved by grace through faith and not by works (Ephesians 2:8-10), God still makes certain moral demands on the political order or the civil government, and on all believers and nonbelievers who live under that political order. The civil government “pertains only to the establishment of civil justice and outward morality,” Calvin asserts, but “is ordained by God (Calvin, 1485 and 1489).” Therefore, we should not think of civil government as “a thing polluted, which has nothing to do with Christian men (Calvin, 1487).” We need the civil government to restrain sin even among Christians, contends Calvin. To think of doing away with civil government “is outrageous barbarity (Calvin, 1488).”

According to Calvin, the civil government “prevents idolatry, sacrilege against God's name, blasphemies against his truth, and other public offenses against religion from arising and spreading among the people; it prevents the public peace from being disturbed; it provides that each man may keep his property safe and sound; that men may carry blameless intercourse among themselves; that honesty and modesty may be preserved among men (Calvin, 1488).” The civil government also ought to hand out justice, deliver the oppressed, protect the alien, the widow and the orphan, stop murder, and “provide for the common safety and peace of all (Calvin, 1496).” Calvin condemns stealing, murder, adultery, and promiscuity. He admits that the Mosaic penalties for such crimes should be geared to the people, time and place, but that times of great social stress require harsher penalties from the state.

Thus, Calvin strongly implies that the Church, as well as individual Christians, should work together to promote these biblical principles concerning the civil government, the political realm ordained by God. Historian John T. MacNeill confirms this understanding of Calvin’s writings. “It was Calvin’s aim,” he says, “to bring religious influences to bear upon magistrates. . . . Calvin attempted to call forth among all citizens a political conscience and a sense of public responsibility. . . . God, he said, should be held ‘the president and judge of our elections’ (McNeill, The History and Character of Calvinism, 187).” (See also pages 224 and 225 of McNeill’s book.) Calvin concludes: “No one ought to doubt that civil authority is a calling, not only holy and lawful before God, but also the most sacred and by far the most honorable of all callings in the whole life of mortal men (Calvin, 1490).”

In “Temporal Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed,” Martin Luther makes the same distinction between a spiritual government or kingdom and a temporal government. He says there will be few people who actually live a truly Christian life. “For this reason,” he declares, “God has ordained two governments (Lull, 665).” Both governments are necessary, Luther contends: “the one to produce righteousness, the other to bring about external peace and prevent evil deeds (Lull, 666).”

Christians may quibble with some aspects of Calvin and Luther's thinking about the Protestant doctrine of the Two Governments of God, but their viewpoint is mostly a biblical one, as passages like Matthew 22:22, Acts 4:19, Romans 13:1-7, and 1 Peter 2:13-17 appear to demonstrate. Our Founding Fathers operated under this same sacred principle, as do many of the people in the so-called religious right do today, however imperfectly.

Americans owe allegiance to the God of the Bible, who informed most of the basic principles of the enlightened, constitutional Christian government established by America's Founding Fathers, in the year of their, and our, Lord, Jesus Christ, 1776 and 1787 (see the conclusions to both the Declaration of Independents and the United States Constitution).

Bibliography:

Evans, M. Stanton. "The Theme Is Freedom: Religion, Politics, and the American Tradition.” Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway, 1994.

Hofstedter, Richard. "The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It.” New York: Vintage Books, 1989.

Lull, Timothy F., editor. " Martin Luther’s Basic Theological Writings.” Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989.

McDonald, Forrest, and Ellen Shapiro McDonald. "Requiem: Variations on Eighteenth-Century Themes.” Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1988.

McNeill, John T., editor. "Calvin: Institutes of the Christian Religion.” Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

-----. "The History and Character of Calvinism.” New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Be First to Comment